The creator of Prince of Persia has written a memoir, but he is not its chief subject, nor is his most famous creation. Replay: Memoir of an Uprooted Family, a graphic novel-style memoir by Jordan Mechner, is a family saga told over a hundred years of European Jewish diaspora. It is as much a biography of Mechner as it is his father, his grandfather, and Lisa Ziegler: Mechner’s great-aunt, and the book’s romantic hero.

Ziegler, an Austrian in her late thirties, kept herself and her young nephew—Francis Mechner, Jordan’s father—alive as refugees in occupied France. From 1938 to 1941, Ziegler shepherded her nephew from Le Touquet to Paris to Nice. She had to feed and clothe him, nurse him through sickness, and even shield his body with hers from German gunfire, all while teaching him to be polite always and never to steal. Amid arrests, deportations and executions, Ziegler found for her nephew happiness in a stamp collection, a snail cooked in garlic, and a walk on the beach. For herself, she found love, only to leave it behind for two seats on the last boat out of Europe. Ziegler tearfully, silently, bidding farewell to her lover, who promises that somehow he will find his way to her in America.

None of this is about video games; really, Replay is not much about them either. There is nothing new about Prince of Persia, nor what Jake Gyllenhaal is like in person. In his heart and on the page, Mechner is far more interested in Lisa Ziegler than Prince of Persia: The Sands of Time (here afforded less than a page)--and this is precisely why Replay is a good book. More than that: it’s what makes him a good game designer, as well.

Readers will learn much more about Mechner as a game designer and an individual in his other books: two published volumes of his personal journals, covering the years 1982 to 1993. That is the story of Mechner’s journey from an 18-year-old hobbyist programmer and film aficionado studiously neglecting his Yale education to an independently wealthy video game auteur. The journals are shot through with a young man’s stubborn sense of romance and guileless wonder that Replay—a grand, ambitious narrative controlled by a man in his late fifties—is too mature to indulge.

The precocious Mechner of the journals prefigures Wes Anderson’s Max Fischer: a cosmopolitan child prodigy whose father is a prominent New York psychologist and brother one of America's best Go players, who worries about turning out like Charles Foster Kane, is mysteriously fixated on whether “chilling the skin increase[s] susceptibility to pain,” notes with a sigh that every attractive woman he meets is already married, and whose plans for the future involve getting into game design once he is “too old to code.”

Mechner introduces the journals with a disclaimer that his younger self thought and wrote things he now finds “embarrassing, cringe-inducing or flat-out wrong.” Nonetheless, it was that younger self who made Kareteka at 20, and Prince of Persia at 25. The wunderkind Mechner who made those games is key to understanding his work and his life since; the journals should be read as a piece with the new memoir.

Reading these journals, though, you marvel that he ever made anything. In love with both arcade games and Hollywood filmmaking, his mind forever vacillates between which vocation to pursue. (May 4, 1983: “To help create a new art form that could become as ascendant as movies are now — now that’s a calling!” May 9: “I don’t want to write computer games! I’d be a good director. I know I would… nothing excites me as much as movies.” May 13: “Just wanted to record that at this moment, the idea of making movies does not appeal to me quite as much as the idea of writing video games.”)

After Mechner lands a hit with the karate adventure game Karateka, published by Broderbund, he frets that working on another game “would take time away from screenwriting”; he wonders if “there will even be a computer games market a couple years from now.” He knows for sure that there is a clock running out on the Apple II game market—the Apple II being the lead platform for Mechner’s follow-up Prince of Persia—and yet he neglects development on Prince for six months to try and get a screenplay produced with the director Curtis Hanson.

With Prince stalled, Mechner mulls a move to Los Angeles to focus entirely on screenwriting, though other screenwriters suggest he is clearly in the right business already. Mechner’s project manager at Broderbund urges him that he has “an extraordinary talent and ability, possessed by only a few people, to actually conceive, design and execute a game all by [himself].” In reply, Mechner nods politely and wonders to himself who he could hire to finish Prince of Persia. Meanwhile, Curtis Hanson is disappointed with Mechner’s script revisions and drops out of the project; the film is never made.

Mechner finishes Prince; it is—eventually—a huge success. As his next move, he applies to film school.

“You dumb shit,” Mechner quotes a friend, Adam Derman. “You’ve dug your way deep into an active gold mine and are holding off from digging the last two feet because you’re too dumb to appreciate what you’ve got and too lazy to finish what you’ve started.”

Stuck between film and games, Mechner chooses both and neither. But even as his path might look obvious in retrospect, you get it. Mechner came to the game industry at a time when he—when anyone—could make a game at home and mail it to a publisher, and receive in response hands-on coaching, support and feedback from the CEO. Compare that to the film industry’s gauntlet of agents, managers, producers and directors, each keeping a different gate—and who’s to say that in another time Mechner would not have been as good a screenwriter as he was a video game designer? Perhaps it is hypotheticals like this that kept Mechner a willing prisoner in the eternal torment of the creatively unsatisfied, not content to be one of the best game designers ever to do it.

Mechner is a dilettante—to his proficiencies in game development and screenwriting he has since added comic books, memoirs and illustration—and he comes off like he lives his life that way, as a bygone literary creation of Henry James or Scott Fitzgerald: the restless American abroad in Europe, learning new languages, living off allowances and remittances, working only when he has to (re: Karateka, “Projects like this should only be undertaken in leisure, i.e. summer”) and eternally hopeful of bumping into beautiful women. (“If I don’t [travel] now I’ll never be able to do it again—not the way you travel when you’re young: looking for answers in everything, hoping to fall in love.” I believe that if Mechner ever saw the film Before Sunrise, he would have had to lie down for a week.) He feels like such a cultivated, old world personality—buying Vivaldi on vinyl, discussing psychology over port in the drawing room, and dreaming of Paris and love and being in love while being in Paris—that when he says something like “What a great movie!” about Gremlins, it is genuinely shocking.

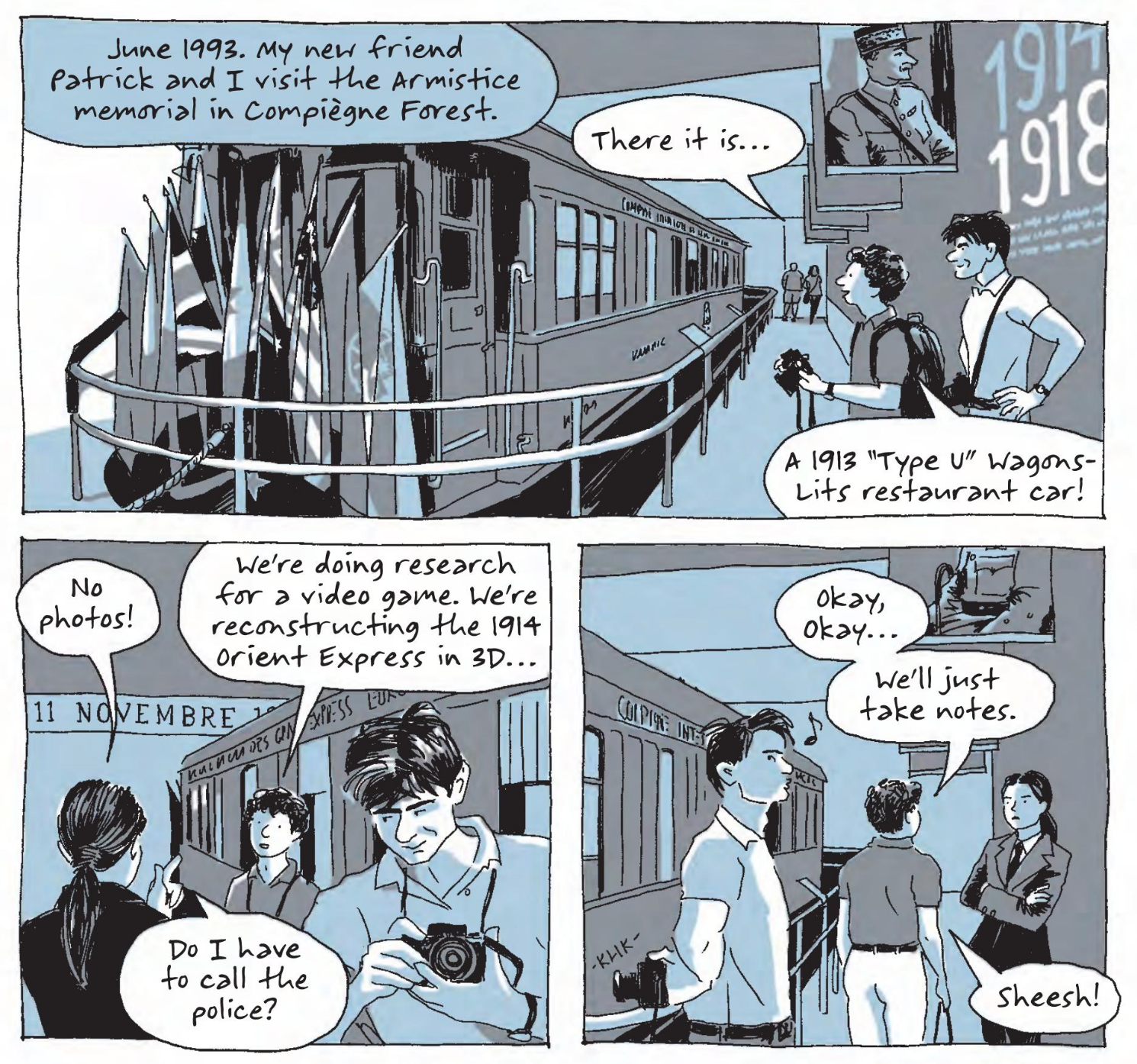

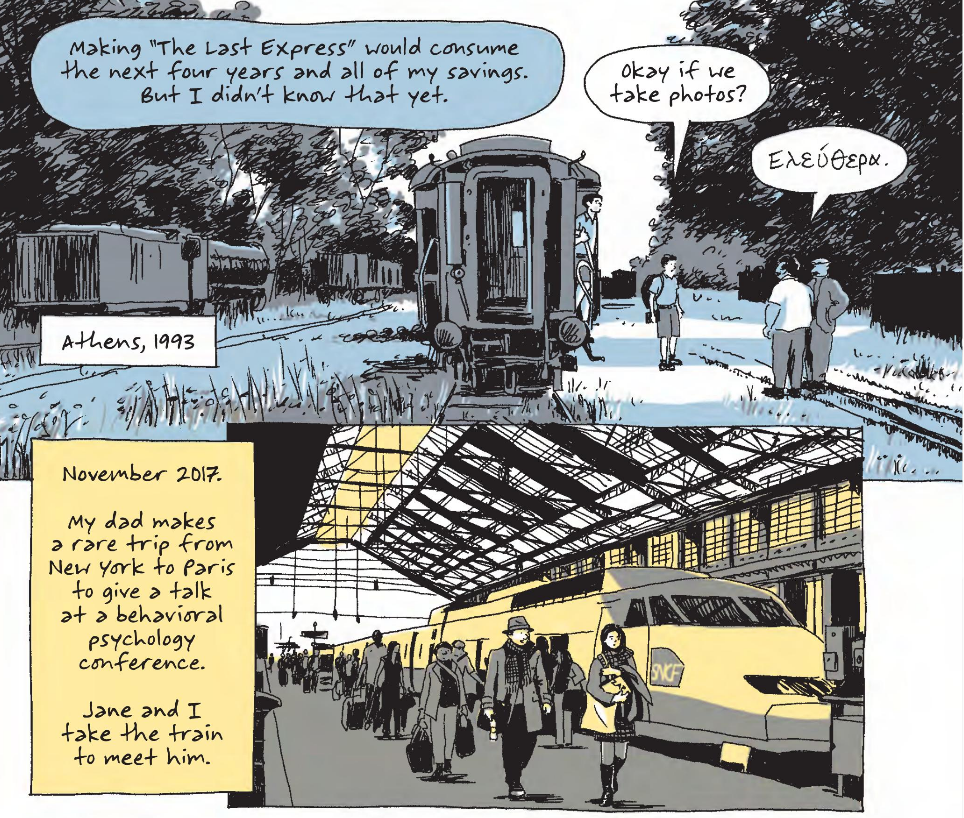

But you will get more interesting games from someone who is interested in more than games. And only a dilettante could be unbothered enough about his Yale education to blow it all up for Karateka, or toss over all the craft he had mastered in Prince of Persia to start afresh with The Last Express, the grand, pre-war Orient Express adventure that wiped out Mechner’s savings. None of what made Prince great—fluidity, clarity of design—is in Express, or vice versa; Express is lush, literary and languid. Prince is the work of a brilliant game designer; Express, a screenwriter with Synecdoche, New York ambition. Prince is a perfect object, Express is not—but it is to Mechner what East of Eden was to Steinbeck. “A box,” Steinbeck wrote. “Nearly everything I have is in it, and it is not full.” The Last Express does not happen if Mechner follows up Prince with a string of sequels from the studio system; it could only have come from a game designer and a frustrated filmmaker, a 19th century romantic, an American in Paris with a paperback Rebecca West, by temperament borne back ceaselessly into the past.

What links Prince and Express is the stress they place on time. The Prince races against the sands of an hourglass; if the player does not finish the game in under an hour, they lose. Express runs in pseudo-real time, and in lieu of a conventional save/load system, the player can turn back the clock to any point; meanwhile, historical irony underscores every moment of the last days before World War I.

The time motif is most prominent in Mechner’s one collaboration with Ubisoft Montreal, Prince of Persia: The Sands of Time. As in Express, the player can rewind time at will; here, however, the story is about this device. Mechner writes in Replay that Sands of Time, coming after the cratering commercial failure of Express, “was a surprise hit. It restored the prince’s fortunes, and mine.” Revivified and relevant in games once more, Mechner sells the Prince of Persia rights to Ubisoft and goes back to movies.

This time, he finally gets a film made, a Prince of Persia film, and he gets it made at the scale of a big studio adventure, like the movies that enchanted his teenage self: like Star Wars, like Raiders, like (yes) Gremlins. His screenplay is rewritten by at least three people, and he is disillusioned with both the picture and the process of large studio filmmaking. The monkey’s paw curls a finger; Lucy pulls the football away from Charlie Brown.

But, you know, what’s the alternative? Should Mechner have wised up, cashed in and spent the next twenty years at Ubisoft, bouncing between Watch Dogs and Assassins’ Creed sequels and Tom Clancy games and long wasted years on Beyond Good & Evil 2—until the idea of Jordan Mechner working on a video game ceased to mean much of anything at all?

Signing up is free!

By signing up—again, it costs nothing!—you can read the rest of "The Long Way Home: Jordan Mechner's Odyssey to the Past," and receive free newsletters and emailed articles from Remap!

Sign up now Already have an account? Sign in