And Roger opens as a horror game and concludes with transporting the player into a puddle of tears. It’s one of the best games I played all year.

It’s also impossible to discuss it without spoiling it. So let’s start there.

And Roger is a story about the decline of a loved one. Not their death, but their dying. It’s about the fairy tale we tell ourselves about what it will be like to die of old age alongside someone, as if we’ll wake up one day and go “well, that’s enough” and flip a switch while we hold hands in bed.

Reality is usually much more cruel. And Roger does not shy away from the cruelty, nor the frailties and failings of caregivers for people who may be losing their grasp on reality.

Sometimes, the change is swift. A person is here, until suddenly they’re not. Other times, it happens over days, weeks, years. The transition is quiet, perhaps hard to notice. But it’s happening. And over time, you come to realize the person you know is no longer fully there.

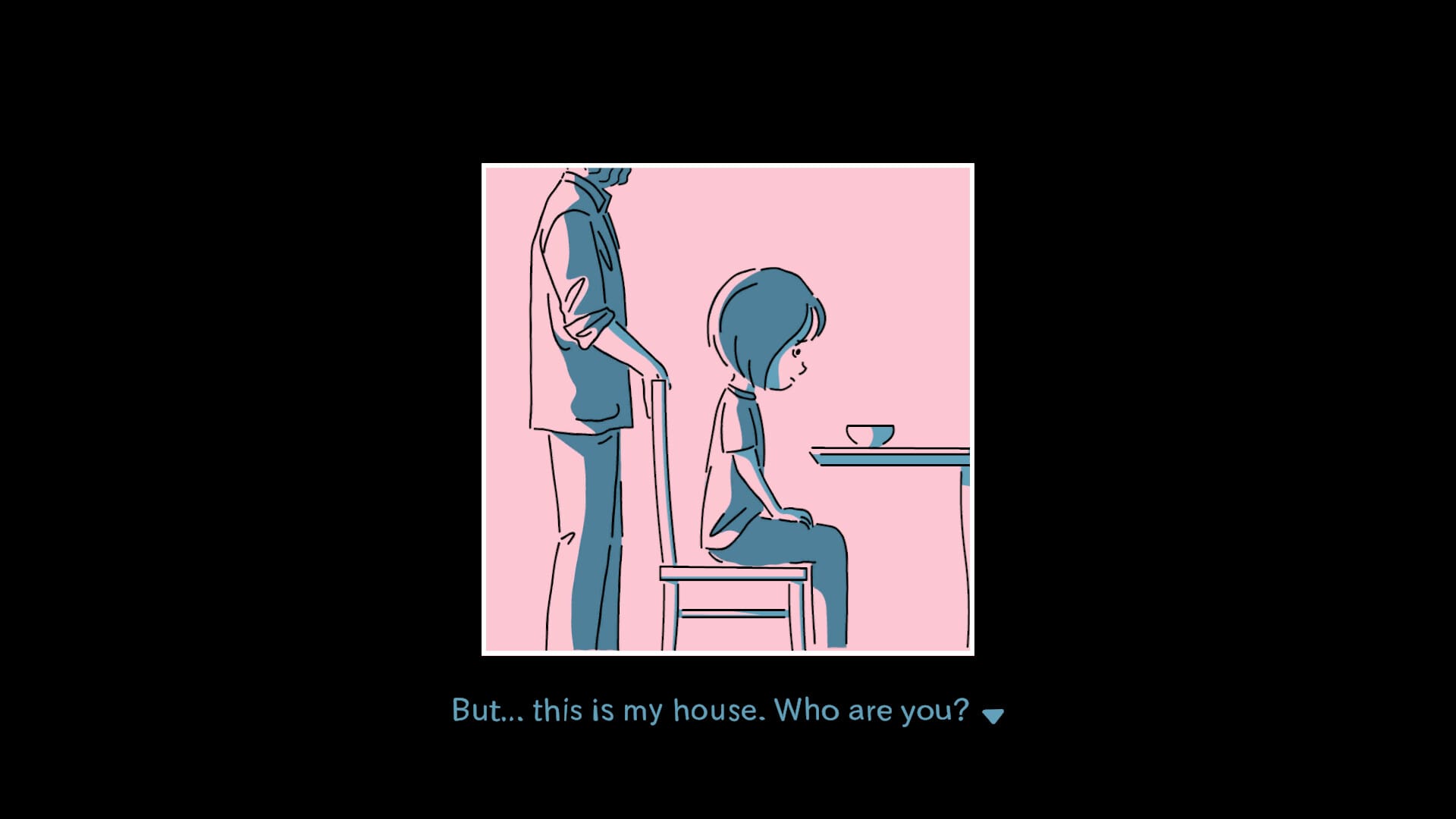

All of this happens in the midst of a game whose design can be reasonably described as a mashup of a visual novel and, of all things, Nintendo’s eccentric mini-game-centric Wario Ware series.

“I wanted the players to take away or feel something from the simple controls provided,” said the designer behind And Roger, who goes by Yona, in a brief email interview with Remap recently.

The game Yona most credits as inspiration, though, is the wonderful game Florence from 2020, which tells the story and the intimate ups and downs of a relationship. It’s one of my favorite games, too.

“I think it’s the most wonderful game I’ve ever played,” said Yona. “It taught me the value of storytelling through games.”

“Expressing the religious aspect of myself is directly tied to my purpose for living. That’s why I have such a strong desire to communicate this message. At the same time, I understand that simply expressing my beliefs as-is won’t necessarily resonate with everyone.”

Other vital touchstones were 2019’s Mosaic (“It was the first time I met a game that felt like ‘art.’") and 2020’s Milk inside a bag of milk inside a bag of milk (“It left a deep impression with its clever use of meta elements and how it crafted a simple yet profound experience.”)

Yona’s last game was the 2D story puzzler In His Time. It‘s thematically similar to And Roger. One Steam commenter said they were “teary eyed towards the end” and that it told a story where “people are imperfect but this game is brilliant.”

“I feel that when gameplay becomes a substitute for words or when gameplay itself begins to ‘speak,’ that’s the key to narrative in games,” said Yona. “That’s why I kept text to a minimum and aimed to make the story compelling through interaction.”

You can see an example of how the game handles this in the clip below, where the player moves items across the screen to represent having a conversation or putting on a ring. Some interactions are very game-like, with ways to win or lose, while others are merely participatory.

Part of Yona’s process was drawing out scenes in “manga-style panels” and sketching each gameplay concept “on paper, one by one.”

“The text sets the direction of the story, and the gameplay expands on and propels it forward,” said Yona. “I think it’s somewhat similar to how musical films alternate between cinematic scenes and music scenes.”

Storytelling—more “traditional” storytelling, anyway—has not come easy to video games. It was only after the medium established itself as something wholly unique, aspiring beyond a premise to addictively munch quarters, that stories became more important to video games as a whole. That was decades ago.

Even now, the question remains: How? (Answer: Insert a sad Dad.)

Games and stories have come a long way, and yet, it’s not hard to wonder sometimes, did this story have to be told here? Could it have been a movie? A book? Why did it have to be a game?

“This might be a disappointing answer, but to be honest, the reason I chose to tell a story through a game is simply because creating a game was the only tool I had,” said Yona.

And Roger feels very personal. You’d naturally wonder if it pulled from personal experiences, because the encounters and emotions are so specific. But Yona said that while his “own upbringing and family experiences had an influence” that “most of the scenes in the game are not direct reflections of my own life.” Perhaps the intimacy of a video game, where you’re pulling the strings set out by the designer, make one feel more susceptible to believing it’s real.

One aspect of the game that is very real, however, is its religious tone. Yona is Christian. The game doesn’t feel oppressively religious, but it does conclude with an excerpt from the Bible:

“And now these three remain: faith, hope and love. But the greatest of these is love. – 1 Corinthians 13:13”

In the moment, I went “huh, you don’t see that very often.” I’m used to killing God—or some kind of god—in video games. It’s rare that you see religion, Christianity or otherwise, used as theme.

“Expressing the religious aspect of myself is directly tied to my purpose for living,” said Yona. “That’s why I have such a strong desire to communicate this message. At the same time, I understand that simply expressing my beliefs as-is won’t necessarily resonate with everyone.”

At its core, And Roger about another, more universal form of faith: love. And a belief that love, whatever comes, can break through.

“What’s important, I think, is not that I present the message directly,” he continued, “but that I create an experience where the player can come to understand or see it themselves through their own personal experience. While I can’t control how players interpret it, I believe that’s something I should entrust to the power of God.”