1.

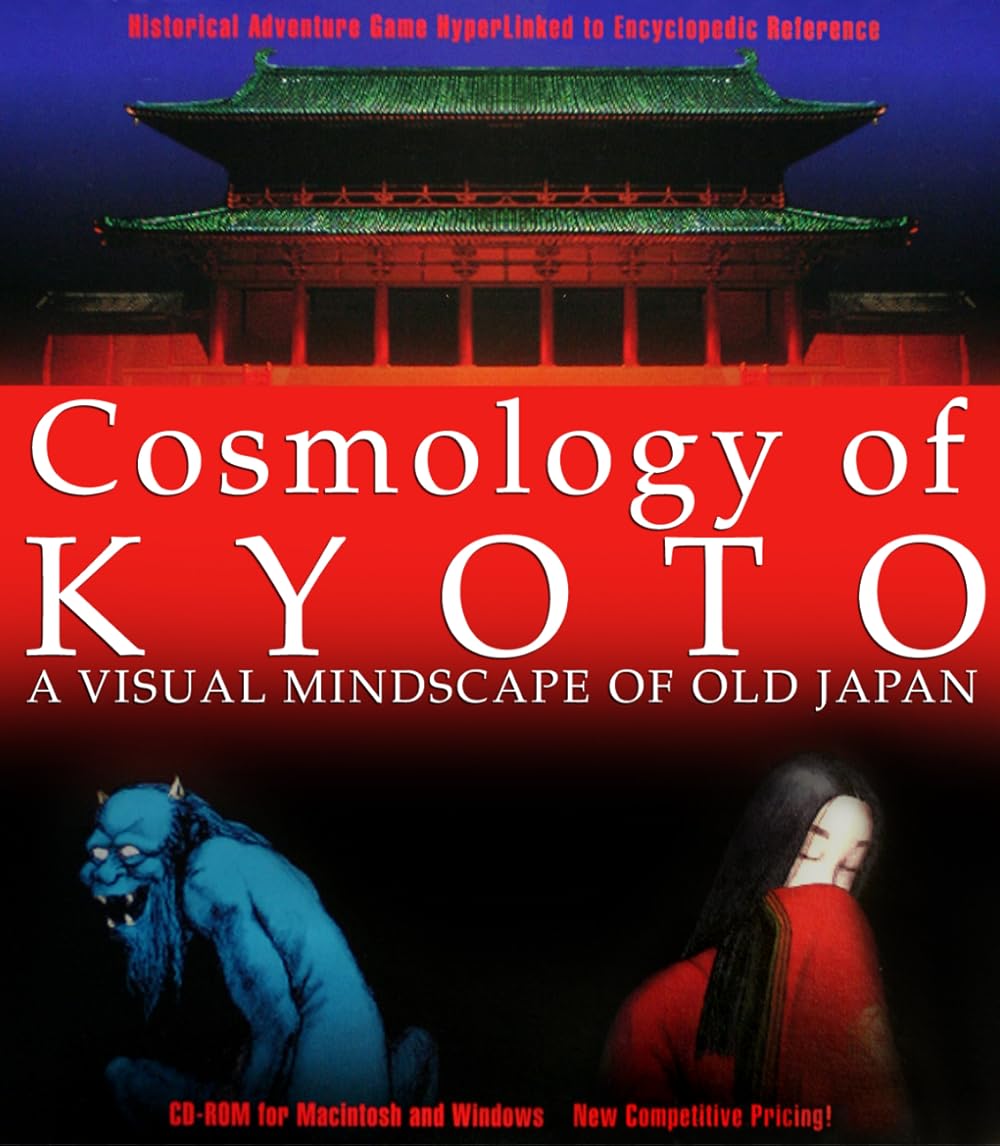

It is thirty years since the publication of Cosmology of Kyoto, which may or may not be a video game. Cosmology, an executable on a CD-ROM produced by a small Japanese team, is a virtual tour of Heian-era Kyoto, a literal encyclopaedia of Japanese history, culture and demons, and a kind of Buddhist religious instruction. The documentation packaged on the CD-ROM does not call Cosmology a video game; it calls it a zone of consciousness.

The zone of consciousness has no object or goal. The player’s journey is set, simultaneously and irreconcilably, over three hundred years of history, infinite lifetimes, and one night, where the angry ghost of an exiled minister has unleashed hell upon the streets of the new capital. Demons, big and small and blue and black, chew on maidens in forbidden houses. Dogs bark. Thunder cracks. Despite it all, the culture is thriving. The player bears witness to supernatural phenomena and horrific violence, buys things they do not need, and dies repeatedly, each time travelling to the afterlife and returning in a new body.

“You just go through this until you finally get it,” Phil Brattain, the sales and marketing manager for Dynaware, Cosmology’s North American publisher, told me. At the end of the game the player ascends to the Buddhist Pure Land. But that’s not the end, Brattain said. “Heaven is not the enlightenment. So what is the enlightenment? You wake up. And you’re out of the game.” It is, I guess, a game won by moving past the need to play it: if you wake up in the game, then you wake up in real life.

Even as Cosmology coaxes a player towards enlightenment, the game is, then and now, strikingly, endearingly obscure. “The space that is Kyoto works like a mirror that projects the depths of the human mind. And it is about to become the mirror of your mind,” goes the game’s opening text crawl. “A thousand years across time and space, a psychic journey begins.” Toshi Ide, the president of Dynaware, thought the game would find appeal with “American new age audiences.”

It did not really crack that audience, Ide says. In fact, Cosmology’s greatest champion has proved over time to be a Roman Catholic, once denounced on behalf of gamers as “determined to be on the wrong side of history [and] the wrong side of the human drive to create”. But Roger Ebert is still the best friend this game ever had, even in death.

2.

At thirty, a long and lasting part of Cosmology’s legacy has proven to be its review by Roger Ebert, a critic notable among many other reasons for not generally appreciating video games. Cosmology is the only game Ebert ever reviewed, though not the only one he ever played. He also tried Myst, another CD-ROM sensation released the same year, for which he “lacked the patience”, though he preferred it and Cosmology to “the kind of computer games where you bop enemies on the head, fry your opponents, and shoot your way through to some kind of treasure.”

Ebert reviewed the game for Wired in September 1994. “This is the most beguiling computer game I have encountered,” he wrote, “a seamless blend of information, adventure, humor, and imagination - the gruesome side-by-side with the divine.” The piece was one of his very few contributions to the (then very young) magazine: he also, briefly, reported on a trip to a Tokyo arcade and panned a TV show. Wired’s executive editor, managing editor or associate editor from that time don’t remember exactly why Ebert wrote these. “As I recall,” says Mark Frauenfelder, then the associate editor, “he would email me and tell me he was excited about something”. Those emails no longer exist; the editors rued their lack of access to their old Wired emails. “What stories those would tell!”

Ebert’s review of Cosmology highlighted the apparently aimless wandering and witnessing; his report is of an experience not unlike his visit to the arcade. “I love to walk city streets - exploring London has been my obsession for years - and I never think much about where I’m going. I walk up this street and down that, finding places I didn’t know I was looking for,” he wrote of Cosmology elsewhere. “Cosmology of Kyoto creates the same kind of experience, and is curiously absorbing; at some level, I am not playing a CD-ROM-based computer game, but venturing down the threatening, promising streets of an unknown city.”

Cosmology let Ebert approach video games as a Dickensian wanderer: the spirit within him walking among his fellow men, travelling far and wide and responding to the world with wonder. “In this medieval Kyoto,” he wrote, “people exist alongside ghosts, demons, and goblins. On my travels I have met—and interacted with—a dog eating entrails, long-winded old farts, tradespeople (who offered me medicines, dried fish, cloth, rice cakes, amulets, and a chance to lose money on a cock fight), a monk leading a prayer meeting, kids playing ball in the streets (one is beheaded by a passerby), a friendly guide dog, a maiden with an obscenely phallic tongue, and a gambler who taught me a dice game.”

Cosmology starts from the premise that people across time and space are not recognisably the same: if you opened a window on your computer to an unfamiliar land a thousand years in the past, what you saw would be alien and hostile. It is a window, not a bridge. In Cosmology there is no explanation of who you are playing as, but I think you are yourself, playing out what would happen if you really were transported a thousand years into the past anywhere in the world: you would not understand what was going on and you would very quickly die. But there is nothing cynical or mean about that death, because by dying in the way that you have done, you have learned something. That was going to land very well for someone like Ebert who wanted to visit a new place and understand it through the acts of exploration and observation. A video game could be a new place, and a review of it a travelogue.

“I thought about those works of Art that had moved me most deeply,” Ebert wrote once. “I found most of them had one thing in common: Through them I was able to learn more about the experiences, thoughts and feelings of other people. My empathy was engaged. I could use such lessons to apply to myself and my relationships with others. They could instruct me about life, love, disease and death, principles and morality, humor and tragedy. They might make my life more deep, full and rewarding.”

Ebert might have considered Cosmology to be that kind of art, but where a video game is distinct from other forms of art became evident to him in 2010, when he bought a used copy of the game on CD-ROM and discovered it was unplayable on modern computers. The city was gone.

Signing up is free!

By signing up—again, it costs nothing!—you can read the rest of "A World of Lost Souls: Roger Ebert, Cosmology of Kyoto, and Gaming's Hollow Victory," and receive free newsletters and emailed articles from Remap!

Sign up now Already have an account? Sign in