Megalopolis has a lot of mind and more on its shoulders. It is the presumptive capstone to Francis Ford Coppola’s 60-year career in film, the showpiece for which he has traded his long-running wine business, an 85-year-old’s sincere message of hope for the future of this world, and–unexpectedly, tragically–a dedication to Coppola’s late wife and collaborator of 61 years, Eleanor. It’s hard not to be moved by that dedication as the credits roll. But there’s also a brief pang: of all the films Coppola could have dedicated to her memory, Megalopolis is the one offered in tribute, a deeply silly paean to traditional virtues and structures, comforting itself that in the face of seemingly terminal decline and advancing evil, love will save us. “Dover Beach” but self-financed to the tune of 120 million dollars and featuring a scene where Aubrey Plaza plays a character named Wow Platinum who gets eaten out by Shia LeBeouf.

There is perhaps nothing quite so ominous about the opening minutes of Megalopolis than its clear debt to The Fountainhead, and specifically King Vidor’s misguided 1949 adaptation starring a thoroughly out-of-his-element Gary Cooper as Rand’s great hero, Howard Roark. Coppola’s equivalent is Adam Driver’s Cesar Catilina, shown here bestriding the skyline like an Olympian god before heroically dynamiting public housing.

Catilina, a polymath architect and engineer, has discovered a marvelous new material, megalon, that will enable him to build an urban utopia–a megalopolis, if you will–thanks to megalon’s power to resist and even reverse entropy, outlive the doomed decadence of his New Rome. (New Rome standing in here for New York, apparently in an alternate timeline where Tinto Brass’s Caligula remade American culture so thoroughly that forty years later the hottest thing going is still two girls with Roman maiden perms making out on top of a limo.) Megalon enables new architectural forms, like towering buildings that grow from the land like sequoias and coral, and incredible experiments in urban mobility like… moving walkways and escalators. But it is also the stuff of the gods, a sticking plaster for the body and spirit that can restore a shattered body and mind to perfect health.

Who would fight against re-founding society on the basis of megalon? Catilina’s adversary, Cicero (Giancarlo Esposito), the mayor of New Rome, who is rooted in the material present in contrast with Catilina’s focus on the immortal future. He is a well-meaning but overmatched functionary: late in the film, his daughter Julia (Nathalie Emmanuel) sees him not as a powerful ruler but a man mired in quicksand filling his office, blissfully doing paperwork at a desk that is canted downward like the deck of a sinking ship.

Julia becomes the chief point of contention between the two men, as she falls in love with Catilina right after he tells her what a vapid piece of crap she is. Here we must give credit to The Last Jedi: it recognized that Adam Driver or no, this is not the play. But here, Julia is a high-spirited woman-child who lets herself be guided by Catilina and in return functions as his muse. Grimly, the thing that breaks through their impasse is when she spies a child’s playset in Catilina’s office and he encourages her to play with it herself, awakening her to the beauty of his vision while revealing that she is sufficiently elevated to understand the future he seeks to build.

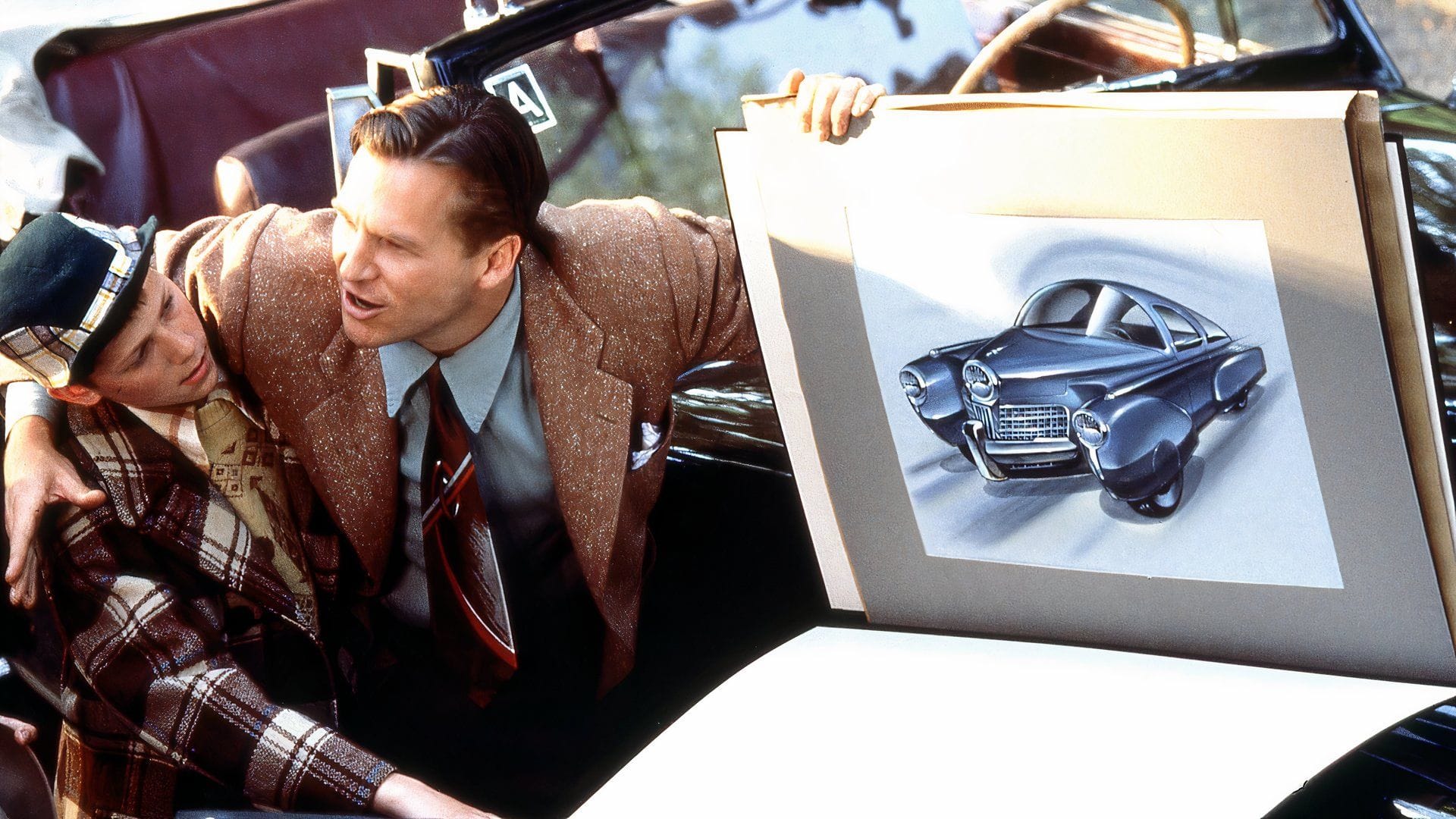

But Julia discovers that far from being a man of the future, Catilina’s eyes are locked on the past. In this he faintly echoes Coppola’s version of George S. Patton, another lonely visionary alternately inspired and haunted by what he sees through the veil of history: a world of Roman and Carthaginian triumphs and the glorious, pitiful dead baking in the Mediterranean sun. As the forces of reaction line up against Catilina and his brilliant creations, I was reminded most strongly of Tucker: A Man and His Dream, a movie I’d forgotten Coppola directed, where a lone auto designer finds himself the enemy of his industry because he dares to build the kind of better, safer car that Detroit loathes.

That film, more modest in its goals, was a more persuasive portrait of a capable dreamer with all the forces of malicious complacency and greed aligned against him–in part because his dream was easy to understand. Catilina’s vision of megalon and megalopolises is juvenile in its principles and its specifics: he is going to build a great, 15-minute city with moving walkways and buildings that look like Krypton by way of Hudson Yards’ Vessel. But the city doesn’t really matter, Catilina hastens to assure Julia and the audience at one point. What matters is the conversation about the city. At the climax of the film, Catilina wins the people over with a direct address from atop a coral-like prominence in his model megalopolis, intoning that what we need is a great debate about the future, in which all take part. It’s a prayer for democratization and civility from a character who seized control of the public square and public space and remade it in his image, but who thinks in opening the comments section he is saving civilization.

Driver and Esposito are good enough performers to make horrendous material almost workmanlike if they fully commit, and indeed, they prove a pair of sirens who lured Coppola away from the salvation of a rewrite. A good moment, suggestive of a better picture, arrives when Julia attempts to bring Catilina and Cicero together over a family meal. Catilina decides to engage the old man in a debate. His opening salvo sounds neat enough, and Cicero smiles appreciatively at the gesture before informing Catilina that he’s misidentified who he is quoting. “Mis-quoting, actually,” Cicero adds with a condescending little smile, before offering a rebuttal from Marcus Aurelius. For a moment the characters have the gravitas the film so often struggles to attain. If you have the option of putting Driver, Esposito, Emmanuel and Kathryn Hunter (playing Cicero’s wife) around a table to hash out their litany of issues, couldn’t that be 80% of the picture? Shouldn’t it be? You wonder how much better it might have been if the film had given free rein to its Shakespearean impulses rather than settling for quotation and pastiche.

But the intellectual pretense of Megalopolis is just that. The characters have so little to actually say. They just keep quoting Aurelius, the Roman philosopher-king who became so fashionable in recent decades, especially among the super-rich of Silicon Valley. Immediately you can see why Coppola fared so much better with The Godfather. Puzo’s novel had Machiavelli and Caesar and Augustine lurking in the background of every scene, but he knew it’s better if instead of quoting them a character just pulls out a gun and whacks somebody. Adapting him, Coppola threw out most of the speeches in the book and trusted filmmaking and acting to get the thrust across. With Megalopolis, it’s the opposite. When the character's have an idea, it feels like to get it across they have to sneak glances at copies of Bartlett’s between shots.

Coppola’s love for the material is evident. Megalopolis is bursting at the seams trying to fit in all the bits of moviemaking he adores. The element of Coppola’s filmmaking that I think is most satisfying here is that frequently and unashamedly works with the kinds of shots and sets that defined the silver screen filmmaking that the death of the studio system and the arrival of Coppola’s generation helped consign to history. If so much of Megalopolis is going to be filmed on soundstages with digital mattes, the scenes might as well evoke old movie sets: Catalina’s office is dressed and redressed to be a lavish Art Deco study, a cozy floating nest, and a bustling dream factory. An evening drive through the city takes on an otherworldly cast using reverse projection, the characters seeming to drive through a movie playing outside their windows.

Library, Zeal or Foundation tier

Subscribe at Library, Zeal or Foundation tier(s) or above to access "A Folly in the Roman Style". You'll also get access to the full back catalog of that tier's content.

Sign up now Already have an account? Sign in