To quote a phrase I’ve overused on Remap Radio lately, and is used again later in this piece (!!), I love puzzle games until I don’t. It’s a genre that I have the most love/hate relationship with, perhaps because it’s the fastest way to reveal the weaknesses in my brain that frustrate me.

At Waypoint, I wrote about this while playing Paper Mario: The Origami King. It’s a terrific game, but forced a confrontation with a problem I’ve had my entire life, and the game is built around it:

As a child, I never knew what to do with a random stack of LEGOs, but hand over some directions and I could build anything. In high school, algebra made sense. You follow the formula, and it’s basically impossible to screw up. Geometry, though? Bane of my existence. I sprinted towards an easy A in algebra, while barely holding onto a C- in geometry. My inability to understand how to geometry single handedly sunk my otherwise good ACT score.

Normally this is whatever, but it’s presented a huge problem recently, because I’ve been playing through Paper Mario: The Origami King, the latest in Nintendo’s long-running RPG franchise. The Origami King is all about looking at, analyzing, and really internalizing the shapes presented to the player, in order to be successful at the game’s unique combat system, wherein players manipulate a circle to try and line up and bunch enemies together.

Maybe this is, ultimately, my downfall with puzzle games writ large: shapes are bad?

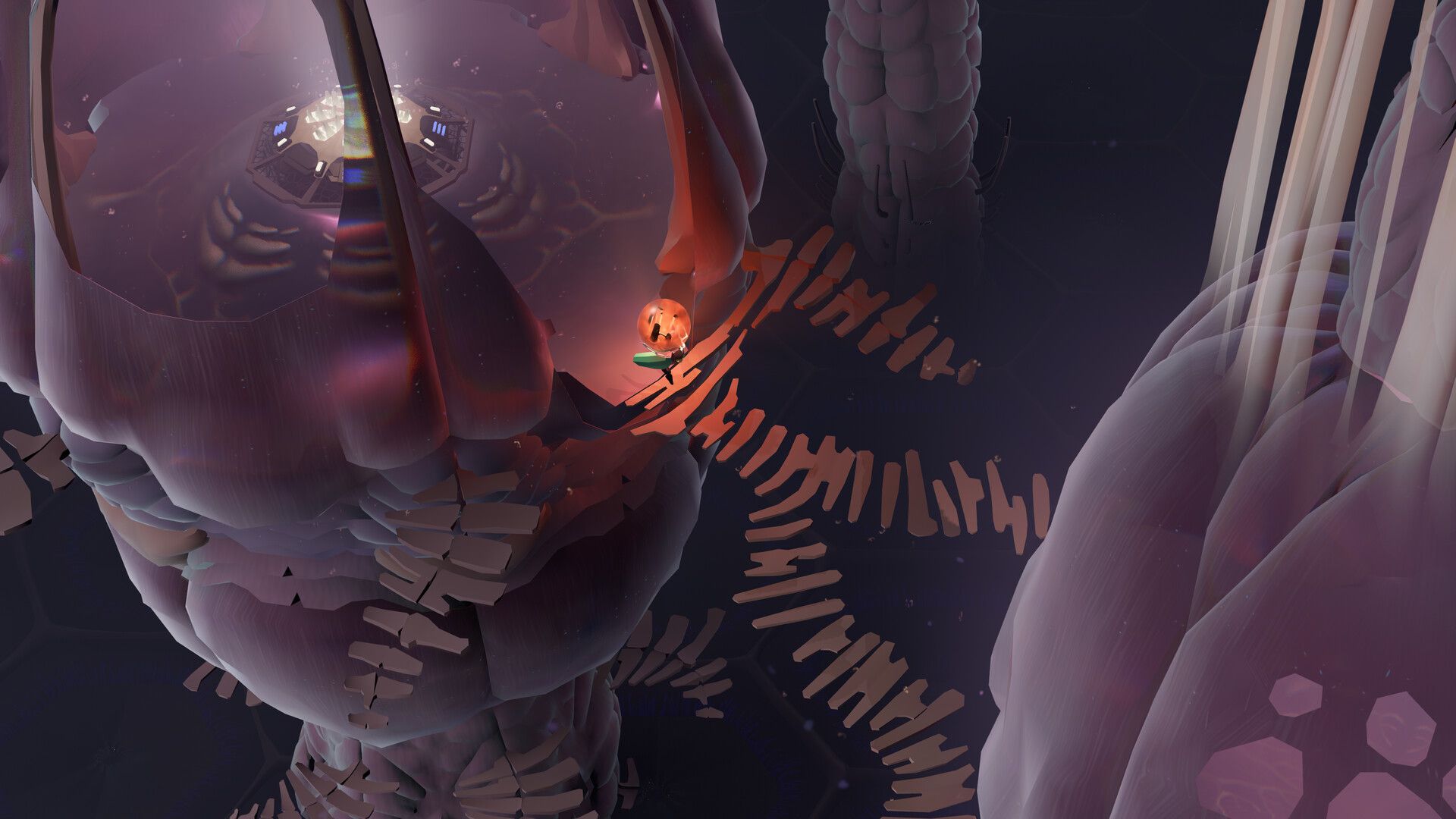

Cocoon, however, is very good. It’s one of my favorites released this year, and comes right after another terrific puzzle game, Viewfinder, also managed to walk a fine line with me (and my brain), in which I experienced a constant sense of satisfaction without frustration. Which isn’t to say the games weren’t challenging, or didn’t present situations where I could do little more than stare at the screen and go “huh,” but soon enough, I would make progress. It would all click.

When I play a game like this, my first instinct is to email the people behind the game, and see if I can ask some questions. Until recently, there wasn’t much reason to ask those questions, beyond personal curiosity, because Remap didn’t have a website. Now, Remap not only has a website, but starting today, we’re premiering a new and regular podcast series where we’ll be chatting with game developers about what they’re working on, and how they put them together.

So, step one: listen to this podcast with Cocoon’s lead audio director Jakob Schmid and lead art director Erwin Kho in a conversation about everything from being traumatized by movies like Alien and Fire in the Sky, to realizing you grew up next to your creative partner and didn’t even know it. They also talk a whole lot about what it was like building one of this year’s best games!

Then, step two: read my conversation with Cocoon creative director Jeppe Carlsen. I had originally hoped to have Carlsen on the podcast, but he declined. Undeterred, I decided to have my cake and eat it two, and asked if Carlsen would answer some questions over email. He agreed, and it provides some valuable insight into how the different elements—design, audio, art—came together to produce this wonderful game about an insect trying to solve problems.

Remap: I've always described my relationship with puzzle games this way: "I love them until I don't." Which is to say that I wrestle with puzzle design, because it often makes me feel bad when it gets too hard, and that's not a great way to feel playing a video game. What's your own relationship to puzzle games, and how did it inform Cocoon?

Jeppe Carlsen: I think trust is very important when it comes to puzzle games. If I play a puzzle game and I get stumped, then the game needs to have established that solutions are always fair and logical, and that the reward for solving the puzzles feels proportional to the efforts I put into solving them. Personally, I have a very low tolerance for puzzle games that do not create this level of trust, and as soon as I get stumped without trusting the game, I tend to move on to play other things. I think this personal preference has informed COCOON a lot.

Can you talk about the process of refining a puzzle, the journey from an idea you've got kicking around, to watching people actually wrestle with the idea, and arriving at a place where you, and the player, are happy?

Carlsen: The journey for each individual puzzle is very different. My best puzzles tend to spawn when not sitting in front of a computer, but simply from me daydreaming about mechanics and puzzles. Some puzzles just work right out of the gate, while others require a long sequence of iterations through playtesting and tweaks. Through many years of experience of designing and playtesting puzzles, my instincts about what simply works has gotten much better, but it can still be hard to predict sometimes. There is not necessarily a correlation between how complex a puzzle feels to the player, and how long time it took to design it and get it right. Some of the more complex puzzles in COCOON simply worked out of the gate, while other more trivial ones ended up requiring an unexpected amount of iterations.

A lesson in puzzle design is that it is as important to identify all the potential incorrect solution attempts and ideas that players come up with, and then make sure that the player feedback for each of these are as polished as the actual solution(s). Each wrong attempt at solving a puzzle needs to very clearly give the feedback that the solution did not work, that it never will work (with repeated attempts), and why it won’t work. I playtest a lot to identify these different solution attempts that players come up with, and observe and analyze how and what they communicate to the player.

Nothing in Cocoon feels too hard. It also doesn't feel too easy. It's walking this fine line. How do you define that fine line, and how did you keep track of that over the course of making a game over several years?

Carlsen: Playtesting, lots of it. My goal with COCOON was to turn this complex idea of manipulating a hierarchy of worlds within worlds into something very accessible. It somehow felt natural to me, that the more complex the thing I am making is, the more simple and accessible it also needs to be so as not to alienate players. The one button control scheme is spawned from this line of thinking, as well as the very gentle increase in difficulty over the course of the game. I teach everything to the player with careful level design, but I don’t teach anything too explicitly—I rather try to design rooms that are as accessible as possible for the player to reach the correct conclusions on their own.

At some point during development I made a ”mental staircase” for the more mind bending puzzles that requires the player to utilize the hierarchy of worlds within worlds—and then I analyzed each step up: is this the most gentle I can be, or should I move this puzzle further up the staircase? I try to establish and maintain player trust, so that eventually when the game is firing on all cylinders, the player is both fully invested but also expects all puzzle solutions to be logical and fair.

"Each wrong attempt at solving a puzzle needs to very clearly give the feedback that the solution did not work, that it never will work (with repeated attempts), and why it won’t work."

Cocoon feels so...precise. Exacting. You get the sense the game has tons of puzzles and ideas that were thrown out over the course of development, to arrive at the final product, however painfully. Is any of that accurate?

Carlsen: Not exactly. I mean, you always experiment a lot and have to throw out all the early ideas that do not “click” or make the cut, but with COCOON I think it has been more like a constant iteration and improvement of “a whole game”. The worlds and puzzles are very delicately interconnected, and the teaching of rules and mechanics is very gradual, so it eventually felt like I had built a “house of cards” of logic puzzles where removing a card would make the entire thing crumble.

We did cut one large area which was particularly painful since we had gotten pretty far with it. The main reason for this cut was that pacing started to drag from staying in the same world for too long. But furthermore it was cut simply because I observed that we could cut it - the house of cards did not fall when removing it, which makes me ask: why is it then here to begin with?

Finally, what's your favorite puzzle game, and what makes it so special to you?

Carlsen: My favorite game of all time is The Legend of Zelda: Ocarina of Time, which I consider an adventure game but also a puzzle game. It completely changed my gaming preferences and introduced me to everything Nintendo. Even though the game does feel very dated today, I still admire a lot of the game design. A small example I love is how when you enter the first boss arena, nothing really happens, but you notice some small movement at the ceiling. When you then look up with the camera, it quickly zooms in to reveal the eye of a boss and the boss intro cutscene begins. Small details like this feel rather sophisticated even when examined today.

OK, actual final question. You spell Cocoon as COCOON. It's clearly intentional. Does the uppercase mean anything personally, or is it just a style choice?

Carlsen: It makes the C’s and O’s look more like orbs. 5 worlds in the game, 5 orbs in the title/logo ;)