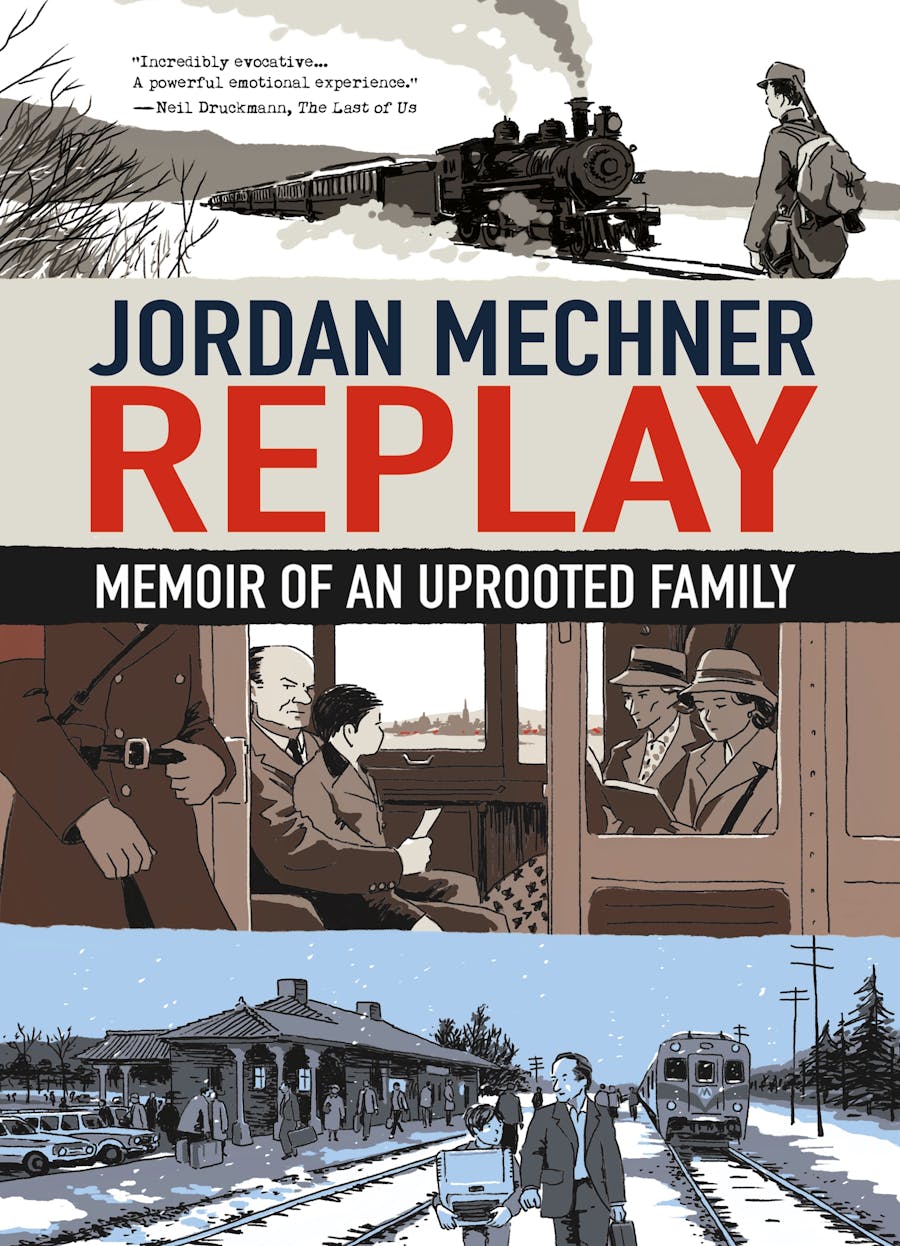

The creator of Prince of Persia has written a memoir, but he is not its chief subject, nor is his most famous creation. Replay: Memoir of an Uprooted Family, a graphic novel-style memoir by Jordan Mechner, is a family saga told over a hundred years of European Jewish diaspora. It is as much a biography of Mechner as it is his father, his grandfather, and Lisa Ziegler: Mechner’s great-aunt, and the book’s romantic hero.

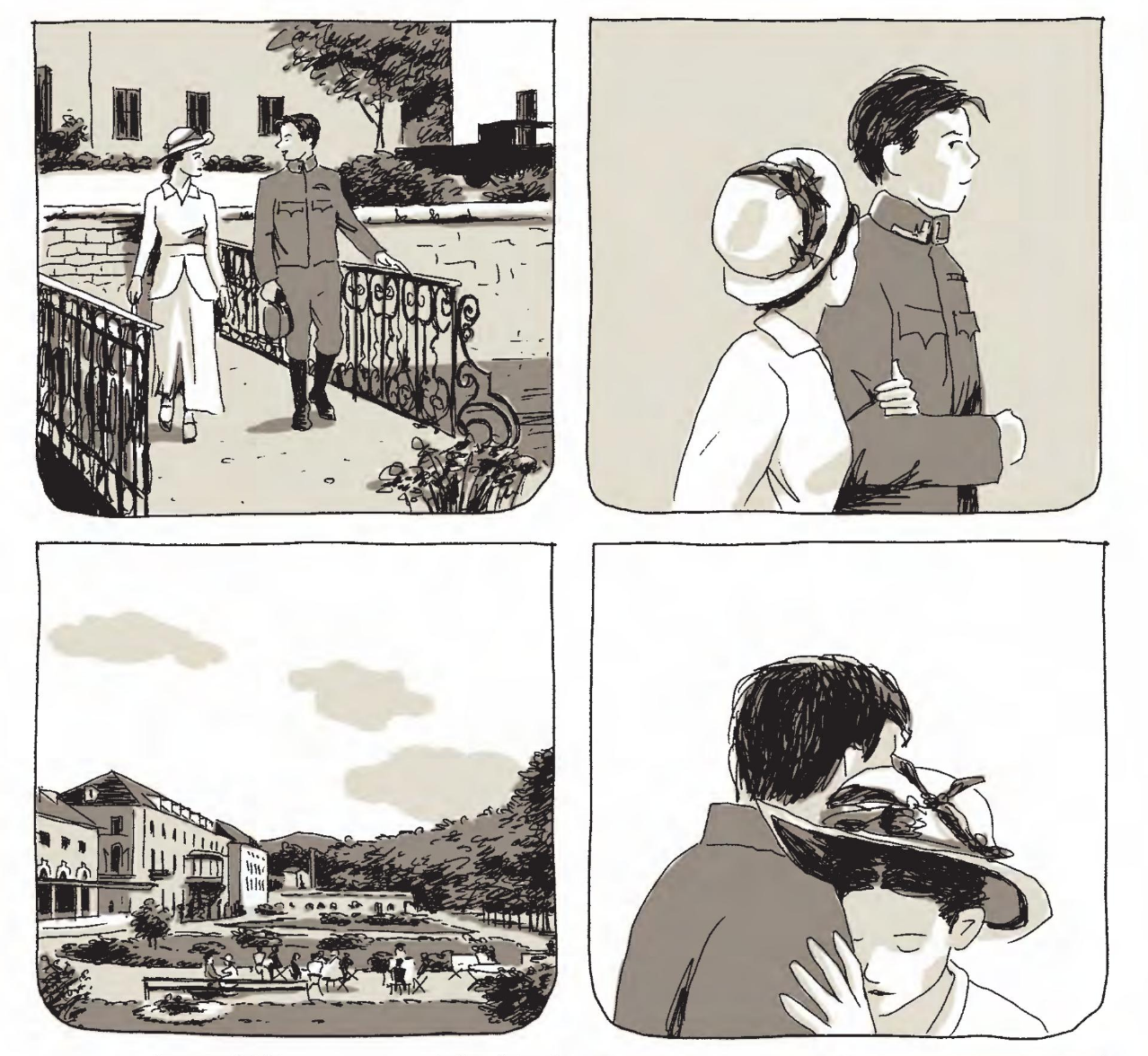

Ziegler, an Austrian in her late thirties, kept herself and her young nephew—Francis Mechner, Jordan’s father—alive as refugees in occupied France. From 1938 to 1941, Ziegler shepherded her nephew from Le Touquet to Paris to Nice. She had to feed and clothe him, nurse him through sickness, and even shield his body with hers from German gunfire, all while teaching him to be polite always and never to steal. Amid arrests, deportations and executions, Ziegler found for her nephew happiness in a stamp collection, a snail cooked in garlic, and a walk on the beach. For herself, she found love, only to leave it behind for two seats on the last boat out of Europe. Ziegler tearfully, silently, bidding farewell to her lover, who promises that somehow he will find his way to her in America.

None of this is about video games; really, Replay is not much about them either. There is nothing new about Prince of Persia, nor what Jake Gyllenhaal is like in person. In his heart and on the page, Mechner is far more interested in Lisa Ziegler than Prince of Persia: The Sands of Time (here afforded less than a page)--and this is precisely why Replay is a good book. More than that: it’s what makes him a good game designer, as well.

Readers will learn much more about Mechner as a game designer and an individual in his other books: two published volumes of his personal journals, covering the years 1982 to 1993. That is the story of Mechner’s journey from an 18-year-old hobbyist programmer and film aficionado studiously neglecting his Yale education to an independently wealthy video game auteur. The journals are shot through with a young man’s stubborn sense of romance and guileless wonder that Replay—a grand, ambitious narrative controlled by a man in his late fifties—is too mature to indulge.

The precocious Mechner of the journals prefigures Wes Anderson’s Max Fischer: a cosmopolitan child prodigy whose father is a prominent New York psychologist and brother one of America's best Go players, who worries about turning out like Charles Foster Kane, is mysteriously fixated on whether “chilling the skin increase[s] susceptibility to pain,” notes with a sigh that every attractive woman he meets is already married, and whose plans for the future involve getting into game design once he is “too old to code.”

Mechner introduces the journals with a disclaimer that his younger self thought and wrote things he now finds “embarrassing, cringe-inducing or flat-out wrong.” Nonetheless, it was that younger self who made Kareteka at 20, and Prince of Persia at 25. The wunderkind Mechner who made those games is key to understanding his work and his life since; the journals should be read as a piece with the new memoir.

Reading these journals, though, you marvel that he ever made anything. In love with both arcade games and Hollywood filmmaking, his mind forever vacillates between which vocation to pursue. (May 4, 1983: “To help create a new art form that could become as ascendant as movies are now — now that’s a calling!” May 9: “I don’t want to write computer games! I’d be a good director. I know I would… nothing excites me as much as movies.” May 13: “Just wanted to record that at this moment, the idea of making movies does not appeal to me quite as much as the idea of writing video games.”)

After Mechner lands a hit with the karate adventure game Karateka, published by Broderbund, he frets that working on another game “would take time away from screenwriting”; he wonders if “there will even be a computer games market a couple years from now.” He knows for sure that there is a clock running out on the Apple II game market—the Apple II being the lead platform for Mechner’s follow-up Prince of Persia—and yet he neglects development on Prince for six months to try and get a screenplay produced with the director Curtis Hanson.

With Prince stalled, Mechner mulls a move to Los Angeles to focus entirely on screenwriting, though other screenwriters suggest he is clearly in the right business already. Mechner’s project manager at Broderbund urges him that he has “an extraordinary talent and ability, possessed by only a few people, to actually conceive, design and execute a game all by [himself].” In reply, Mechner nods politely and wonders to himself who he could hire to finish Prince of Persia. Meanwhile, Curtis Hanson is disappointed with Mechner’s script revisions and drops out of the project; the film is never made.

Mechner finishes Prince; it is—eventually—a huge success. As his next move, he applies to film school.

“You dumb shit,” Mechner quotes a friend, Adam Derman. “You’ve dug your way deep into an active gold mine and are holding off from digging the last two feet because you’re too dumb to appreciate what you’ve got and too lazy to finish what you’ve started.”

Stuck between film and games, Mechner chooses both and neither. But even as his path might look obvious in retrospect, you get it. Mechner came to the game industry at a time when he—when anyone—could make a game at home and mail it to a publisher, and receive in response hands-on coaching, support and feedback from the CEO. Compare that to the film industry’s gauntlet of agents, managers, producers and directors, each keeping a different gate—and who’s to say that in another time Mechner would not have been as good a screenwriter as he was a video game designer? Perhaps it is hypotheticals like this that kept Mechner a willing prisoner in the eternal torment of the creatively unsatisfied, not content to be one of the best game designers ever to do it.

Mechner is a dilettante—to his proficiencies in game development and screenwriting he has since added comic books, memoirs and illustration—and he comes off like he lives his life that way, as a bygone literary creation of Henry James or Scott Fitzgerald: the restless American abroad in Europe, learning new languages, living off allowances and remittances, working only when he has to (re: Karateka, “Projects like this should only be undertaken in leisure, i.e. summer”) and eternally hopeful of bumping into beautiful women. (“If I don’t [travel] now I’ll never be able to do it again—not the way you travel when you’re young: looking for answers in everything, hoping to fall in love.” I believe that if Mechner ever saw the film Before Sunrise, he would have had to lie down for a week.) He feels like such a cultivated, old world personality—buying Vivaldi on vinyl, discussing psychology over port in the drawing room, and dreaming of Paris and love and being in love while being in Paris—that when he says something like “What a great movie!” about Gremlins, it is genuinely shocking.

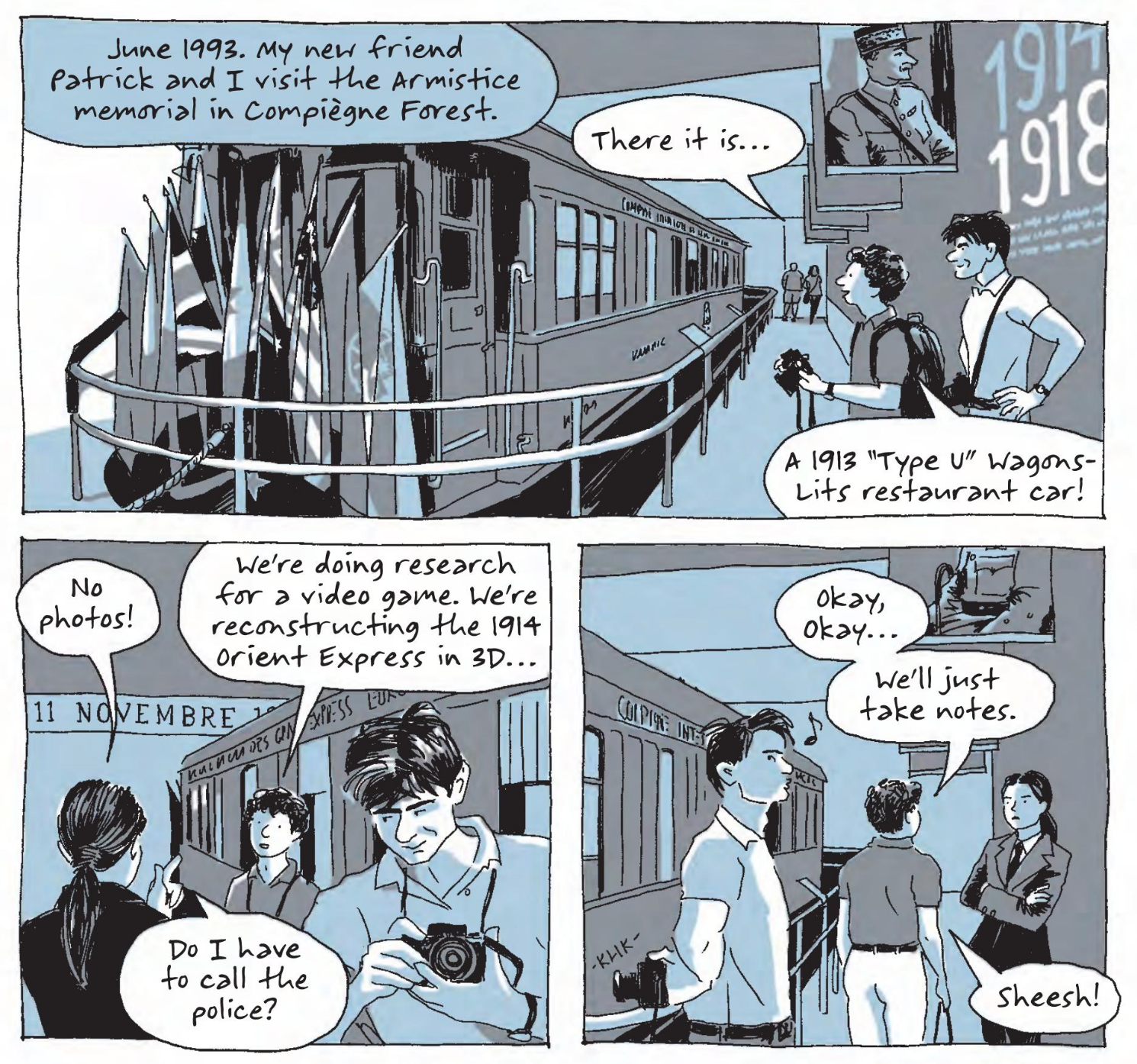

But you will get more interesting games from someone who is interested in more than games. And only a dilettante could be unbothered enough about his Yale education to blow it all up for Karateka, or toss over all the craft he had mastered in Prince of Persia to start afresh with The Last Express, the grand, pre-war Orient Express adventure that wiped out Mechner’s savings. None of what made Prince great—fluidity, clarity of design—is in Express, or vice versa; Express is lush, literary and languid. Prince is the work of a brilliant game designer; Express, a screenwriter with Synecdoche, New York ambition. Prince is a perfect object, Express is not—but it is to Mechner what East of Eden was to Steinbeck. “A box,” Steinbeck wrote. “Nearly everything I have is in it, and it is not full.” The Last Express does not happen if Mechner follows up Prince with a string of sequels from the studio system; it could only have come from a game designer and a frustrated filmmaker, a 19th century romantic, an American in Paris with a paperback Rebecca West, by temperament borne back ceaselessly into the past.

What links Prince and Express is the stress they place on time. The Prince races against the sands of an hourglass; if the player does not finish the game in under an hour, they lose. Express runs in pseudo-real time, and in lieu of a conventional save/load system, the player can turn back the clock to any point; meanwhile, historical irony underscores every moment of the last days before World War I.

The time motif is most prominent in Mechner’s one collaboration with Ubisoft Montreal, Prince of Persia: The Sands of Time. As in Express, the player can rewind time at will; here, however, the story is about this device. Mechner writes in Replay that Sands of Time, coming after the cratering commercial failure of Express, “was a surprise hit. It restored the prince’s fortunes, and mine.” Revivified and relevant in games once more, Mechner sells the Prince of Persia rights to Ubisoft and goes back to movies.

This time, he finally gets a film made, a Prince of Persia film, and he gets it made at the scale of a big studio adventure, like the movies that enchanted his teenage self: like Star Wars, like Raiders, like (yes) Gremlins. His screenplay is rewritten by at least three people, and he is disillusioned with both the picture and the process of large studio filmmaking. The monkey’s paw curls a finger; Lucy pulls the football away from Charlie Brown.

But, you know, what’s the alternative? Should Mechner have wised up, cashed in and spent the next twenty years at Ubisoft, bouncing between Watch Dogs and Assassins’ Creed sequels and Tom Clancy games and long wasted years on Beyond Good & Evil 2—until the idea of Jordan Mechner working on a video game ceased to mean much of anything at all?

“Finish the karate game, make a million dollars, meet a nice girl, go to Hollywood to make a movie, make another million, forge a new art form and become the Walt Disney of the 21st century,” Mechner describes his ambitions at age 19. Sure, let that kid drive the bus for a while. Why not be a dilettante, if you can afford it?

But that is a young man; inevitably, a grown one must take the wheel. (As most adults will do if a child tries to drive a bus.)

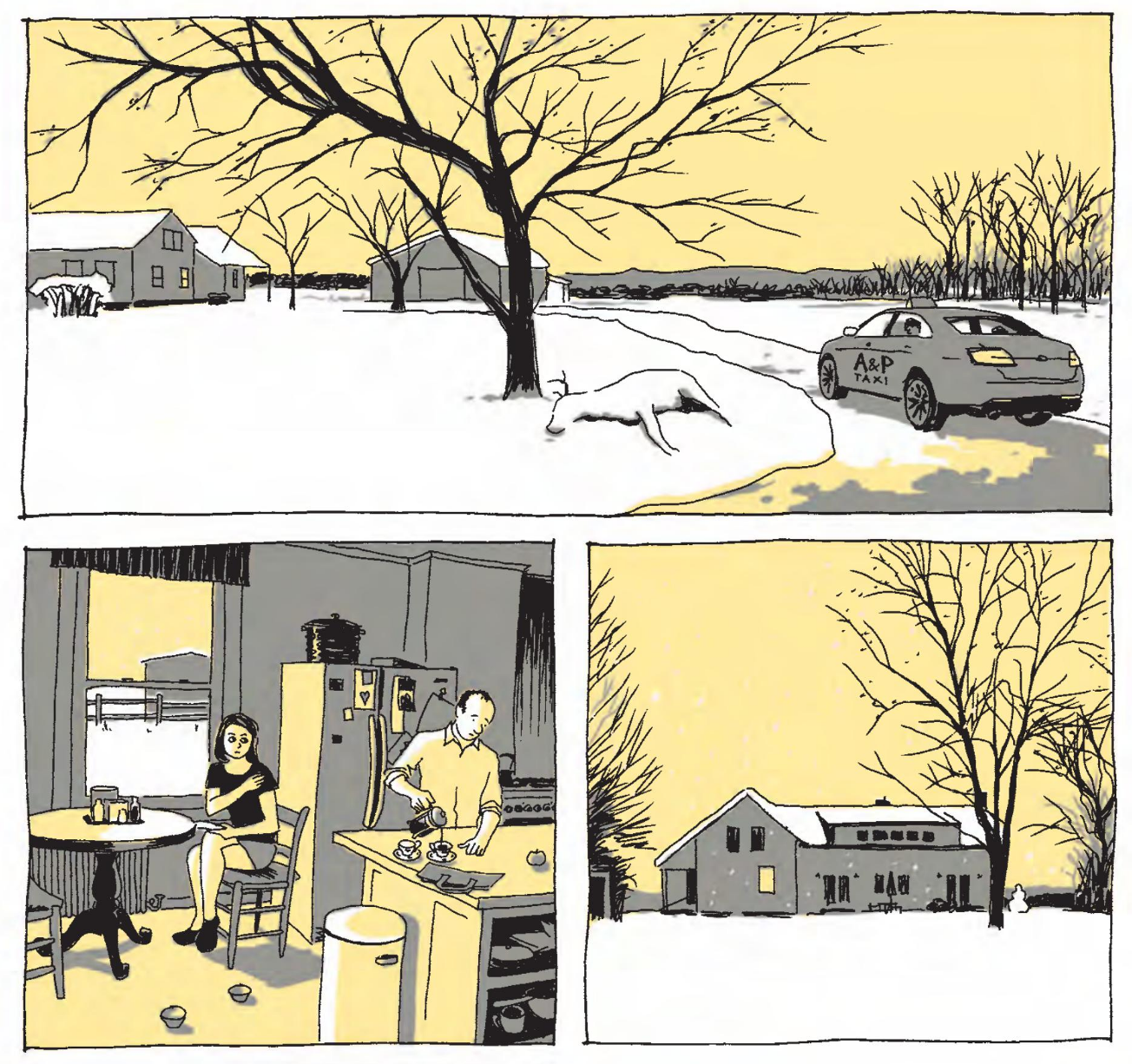

Mechner's memoir, Replay, finds the designer in his fifties; as he tells his brother, David, his dream is no longer Walt Disney and movies but “to get my wife and kids under one roof." Mechner has relocated to Montpellier, France to work on a Prince of Persia game; his teenage children and second wife, the game designer Whitney Hills, have declined to follow him. Consequently, Mechner spends most evenings alone in his Montpellier beach house with a glass of wine and a laptop, digitizing a memoir written by his grandfather, Adolf Mechner–that memoir, never published, is combined here with Mechner's own; the book is really a collaboration between the two men.

“Weren’t you going to do your own memoir?” asks David. “About making games in the eighties?”

“I thought about it,” says Mechner. “But the far past just seems more interesting, somehow. Making games isn't exactly a life-and-death drama.”

It's true, and though there is plenty Mechner has to say about game development over the decades, his most trenchant observation is that the process, then and now, is basically just a bunch of people standing over a monitor asking "what’s good about this” until they run out of money. The last century of Mechner family history supports a far grander story than his own biography allows: a mirrored odyssey, from Europe to America to back. Adolf Mechner leaves Europe to keep his family together; Jordan Mechner returns there at the cost of his family drifting apart.

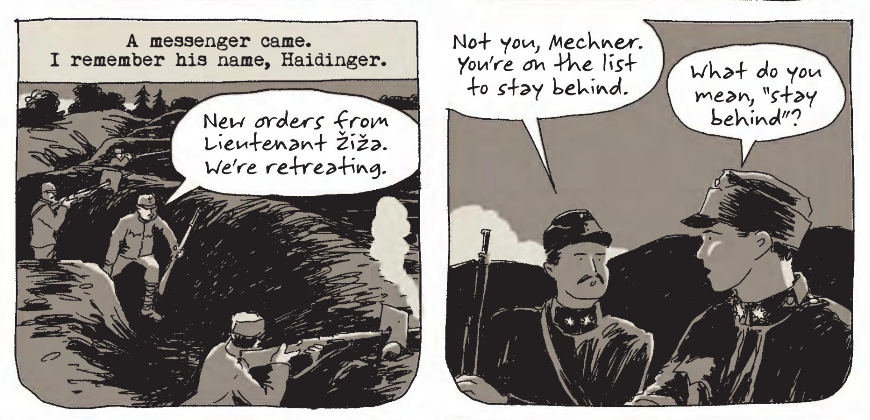

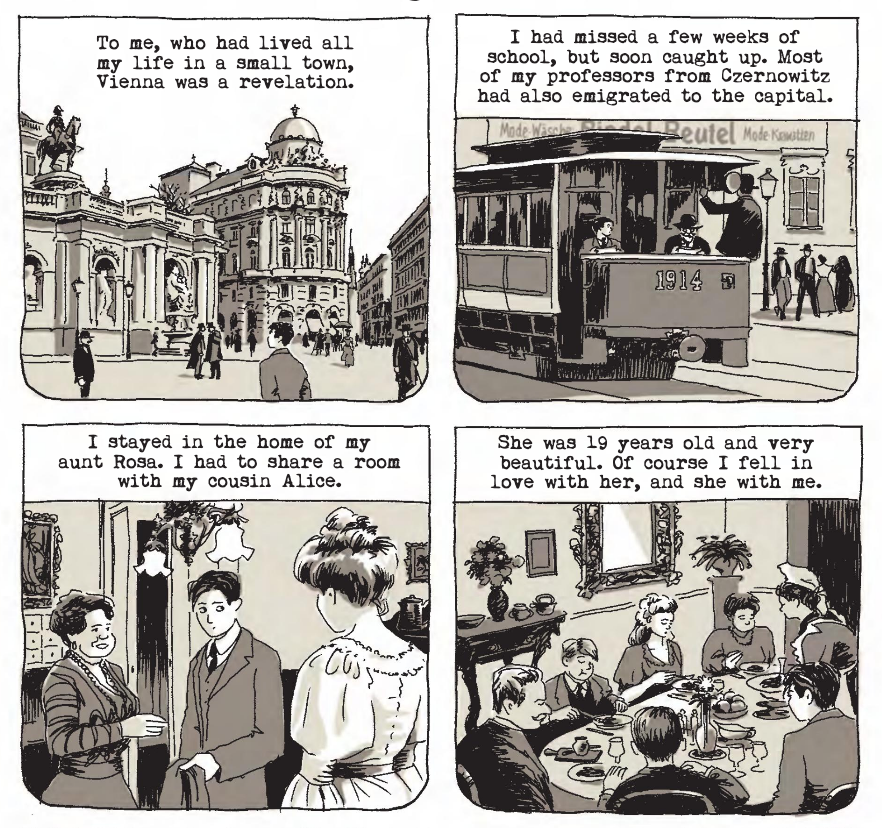

Adolf Mechner was born in 1903 in a place then known as Czernowitz, a part of Austria-Hungary. The urbane Mechners, with roots in Austria and France, are doctors, artists and musicians, educated in Latin and Greek. At parties, they play Strauss waltzes on the piano and contemplate falling in love. In 1915, Adolf enlists and is sent to the Eastern Front, where he is ordered to cover his regiment’s retreat from the Russians by shooting as many as he can before he is captured or killed. Not entertaining this for a second, Adolf immediately abandons the line and reconvenes with the army at a military hospital; when he is asked to what regiment he belongs, he just makes up a number. His gambit works flawlessly, and he is reassigned. The fabric of reality is just so fragile and mutable in the face of bureaucratic caprice; later, Adolf will relearn this to his cost.

In 1938, Nazi soldiers attempt to detain Adolf on his doorstep in Vienna; stalling them, he makes arrangements for his family to flee to the United States. Adolf is denied a visa because, to his surprise, he is not Austrian but officially Romanian: Czernowitz was given to Romania after World War I. This is a huge problem: the United States only issues a few hundred visas a year to Romanians, and there are thirty thousand in the queue before him.

Instead, Adolf departs for Cuba, via Paris, with his son Francis; soon after, supposedly, the Nazis attempt to round him up for Kristallnacht. Adolf’s wife and daughter remain in Vienna to await their American visas—believing they will be safer in the short term for not looking as Jewish as the men. On these assumptions, Adolf leaves Francis in Paris with his wife’s sister Lisa, expecting his wife, once she has her visa, to pick up the boy en route to America.

Nothing works as planned. Francis and Lisa are stuck in France for years, itinerant, furtive and ever surrounded by death. The boy resolves at age nine to consider himself as “already dead,” for “dead people have nothing to fear.” It takes over a year after Adolf’s escape for his wife and daughter to get their visas; they make it to New York and do not join Adolf in Cuba. "I've gathered from various family members’ comments that [she] was bitter and angry at [him] throughout most of their 70-year marriage,” notes Mechner. “He doesn't mention or allude to this in his memoir.”

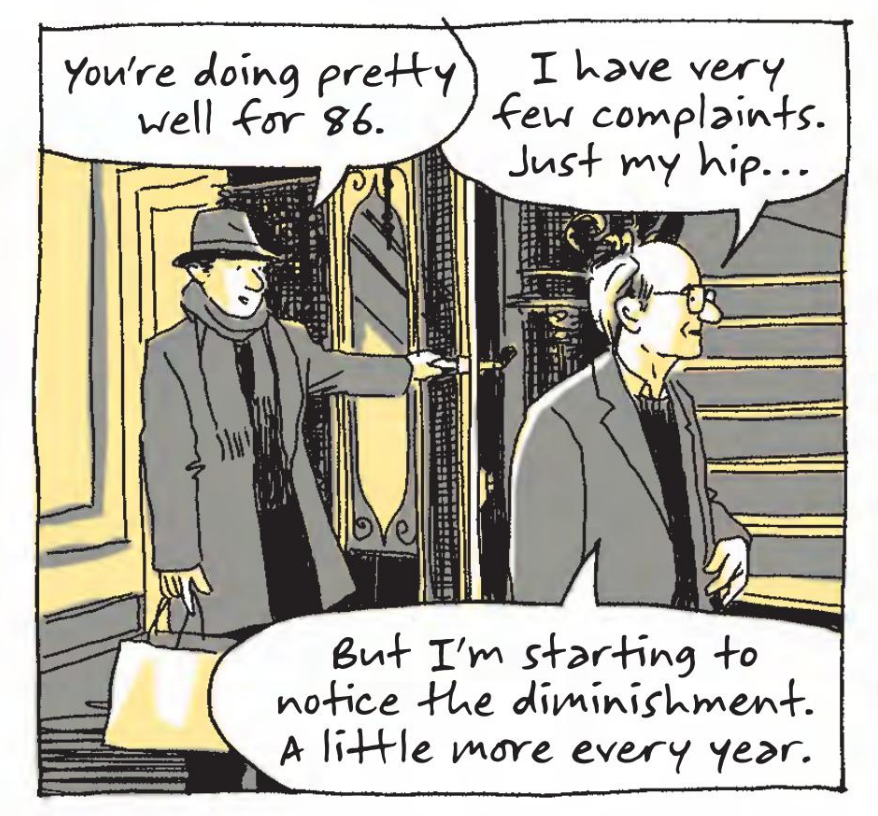

Replay mixes and matches timelines to bleak effect: we see Lisa and Adolf in their prime crash against their older selves in cognitive decline. Francis, as a boy so dependent on them both, mourns them while they are still alive—“She's really going downhill. It's painful to see”; “For me, [he] started dying 10 or 15 years ago”—and after their passings turns to himself.

The book is a requiem, with much to lament: friends, uncles, aunts and cousins who helped Francis and Lisa during the war are sent to Auschwitz and Sachsenhausen, and Adolf Mechner’s parents—he got everyone out of Austria except for them—are killed by the Nazis at Treblinka.

Resulting from the exodus are Jordan Mechner and his siblings, the first Mechners born on American soil. After everything the Mechners went through, Jordan naturally leaves America at the drop of a hat. Mechner first moved to Paris in 1992 (“I’m in Paris. I’m here. I live here. Wow.”) and fell in love with walks on the Seine and French girls smoking cigarettes–not the girls, the image. In 1993, he read Henry James’ The Ambassadors sick in bed (making especial note, perhaps, of this line: “All the same, don't forget that you're young—blessedly young; be glad of it on the contrary and live up to it. Live all you can; it's a mistake not to”) and wrote in his journal, “[This] is giving me a terrible desire to go back to Paris and never leave again…. I need to spend at least six months there. I can’t just let my French life wither and die.”

Mechner remains in Montpellier even after the cancellation of his Prince game in 2019. “I live in France!” he beams on a bicycle in the final pages of Replay; the closest he comes in the memoir to a happy ending. His game is lost, his marriage is lost, his children are thinking about spending some time in Europe–maybe. But: he lives in France!

“Of course, it’s a heartless and materialistic society,” his friend Tomi Pierce told him in 1992, “but it takes you a while to realize that because it’s so beautiful.” Thirty years later, I am not sure that Mechner ever has “realized” that—or if he has, that he particularly cares. Paris is so much more than Paris: it is Europe, it is the past, it is his past—the Mechners’ past.

Mechner’s ideal of European life is a new world dream of the old world: of waltzes in ballrooms, of romance, adventure and long histories. That dream of his was, for a time, his family’s actual waking life—until it turned into the nightmare of the Holocaust Europe was poisoned and torn out of the Mechners and their children still feel the wound. No wonder, perhaps, that the grand past holds such sway over Mechner, even as everyone else in his life appears somewhat impervious. To his father, Mechner wonders if he ought to visit Czernowitz; his father tells him there is no point: “It’s not really there anymore,” he says–and neither is this past. Still. Still, still, still.

“Americans are supposed to be the forward-thinking people,” Mechner’s friend Patrick chides him in Replay. “Why are you nostalgic for a place you never saw?”

Such nostalgia extends to the constitution of Replay itself, a book not just about the past but the idea that the past has value. Replay is an exhaustive work of family anthropology, an opportunity for Mechner to remember his grandfather and great-aunt and father to the world as they were in their prime.

Most striking about Mechner’s approach to Replay is how he sets this work of history against his wife and children–the Americans–urging him to look forward instead. If Mechner’s wife Hills is not the book’s villain, she is an animated spirit inimical to its thesis. She wants to live in an Airstream trailer on a sustainable farm, and moves all of her and Mechner’s mementos, souvenirs and childhood photos into two piles in their house. “It’s old, stagnant energy. The family spaces of the house need room to breathe,” she says. “Getting rid of stuff is incredibly freeing. You should try it.”

The idea to Mechner seems an anathema; no other game developer is selling volumes of their 40-year-old journals. In 2023, the studio Digital Eclipse produced an interactive documentary on Mechner’s Karateka; their editorial director Chris Kohler said that it has never been and will never again be possible to document a game with so much surviving primary source material.

“When my grandparents left Vienna, they spent weeks sorting through their possessions, agonizing over what to pack, what to keep,” says Mechner in Replay. “They loaded a moving van and sent it to Trieste, to ship to New York. Of course, they never saw any of that stuff again.”

“Blessing in disguise,” says Hills. “Just think how much energy that freed up to put into creating a new life together in New York, instead of dwelling in the past. The darkness stored in these boxes is palpable. It's the physical embodiment of your family's shadow energy. Four generations of pain and trauma.”

When Mechner digitizes his grandfather’s memoir, Francis sees it as an urgent work of anthropology to which he wants to add annotations: “I'm the only one left who remembers who these people and places were.” When Mechner does the same with his own journals, Hills notes with implied sarcasm, “Great. Now your entire past will always be available at your fingertips.” Where Mechner’s sympathies lie is obvious; it is no surprise the marriage ends in divorce. (It would be interesting to know what Hills makes of this book; for that matter, where is Mechner’s mother, conspicuously absent in all this?)

“You should make something different instead of just making Prince of Persia all the time,” Mechner’s son tells him. Certainly Replay is, at a craft level, something different—Mechner has not written a memoir before, nor illustrated a graphic novel of any length—but its heart turns back from newness. There is no crisis point in Replay where Mechner is forced to choose between his marriage and his nostalgia; ironically, the pioneer of video game design technology has always lived with one foot in the past.

Like some 19th century conductor in tux and tails, Mechner brings the disparate timelines of Replay to a conclusion of enormous sentiment and operatic emotional power; nonetheless, the book leaves Mechner himself in an uneasy place. What has he learned about managing his attachments to his past as well as those to his present and his future? Well, nothing, exactly. Then again, it is not so important that he does: a memoir steeped in a hundred years of history is certainly truer to Mechner the person than a tight manual on game design and screenwriting.

The past is important, says Replay—and yes, it is. The young Francis Mechner harbors a crush on a cousin and after he leaves her company, sees her name next in the registers from Auschwitz. Adolf Mechner’s very identity is stripped away and traded between nations that are themselves mutating. When Francis urges Mechner not to take a research trip to Iran because the creator of Prince of Persia is a high-value kidnapping target, the idea is at once absurd and urgent: he really thinks he might never see his son again.

Everything can change so quickly, as the Mechners know to their cost. The value of the past, per Replay, is to manage the fear of death, to save some of who and what we inevitably lose to time. (Or: “It’s not so bad as long as you can keep the fear from your mind,” as Twin Peaks’ Agent Cooper says.) Late in life, Adolf has a dream of his death as “a paradise, a reunion with all those people that I loved so much.” Francis Mechner sings nostalgic songs to keep the terror at bay. Jordan Mechner has the streets of Paris, the Gulf of Lion, his boxes, and his ghosts. If they make a wall between him and his present they are, still, what gives this book its power—what gives all his work its power.

Time: that’s where all this power comes from. Life is fragile but time rushes on, and Mechner cannot forget it, declaring in the opening narration of Sands of Time that, "Time is an ocean in a storm". Eventually, we drown in it. Everything drowns in it. But near the game's close, Mechner quotes a poem by Rumi: “Love is life, so if you want to live, die in love. Die in love if you want to stay alive.” So die then. Die in love with the streets of Paris, with Henry James and girls with cigarettes, sure, but best of all with the people who can love you back. If you are Lisa Ziegler or Adolf Mechner, then you died in love, and through love the world has found you again.